Ab Initio [Latin] - From The Beginning

The truth of history, so much in request, to which everybody eagerly appeals, is too often but a word. At the time of the events, during the heat of conflicting passions, it cannot exist; and if at a later period, all parties are agreed to respect it, it is because those persons who were interested in the events, those who might be able to contradict what is asserted, are no more. What then is, generally speaking, the truth of history? - Napoleon Bonaparte (Mémorial de Sainte Hélène: Journal of the Private Life and Conversations of Emperor Napoleon at Saint Helena)

Ignaz Semmelweis: The Pioneer of Handwashing

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (July 1, 1818 – August 13, 1865), a Hungarian physician, left an indelible mark on medical history through his groundbreaking work in infection control. On July 1, 1846, Semmelweis was appointed assistant to Professor Johann Klein at the First Obstetrical Clinic of Vienna General Hospital, a role akin to a modern-day chief resident. His responsibilities included examining patients before Klein’s rounds, overseeing complex deliveries, and mentoring medical students.

At the time, maternity clinics in Europe were established to combat the tragic practice of infanticide, particularly among underprivileged women, including prostitutes, by providing a safe place to give birth. However, the First Clinic at Vienna General Hospital, staffed by doctors and medical students, had a grim reputation. Its maternal mortality rate was a staggering 10%, compared to just 4% in the Second Clinic, which was run by midwives. The disparity was so notorious that some women preferred giving birth on the streets rather than risking death in the First Clinic.

Semmelweis was troubled by the high rates of postpartum infections, known then as childbed fever, plaguing his clinic. A pivotal moment came in 1847 when his friend, Jakob Kolletschka, died after accidentally nicking his finger with a scalpel during an autopsy. The autopsy revealed symptoms strikingly similar to those of the childbed fever victims. This tragedy sparked a revelation for Semmelweis. In an era before the germ theory of disease, he hypothesized that "cadaverous particles" were being transferred from autopsies performed by doctors and students to maternity patients. Notably, the Second Clinic, where midwives did not perform autopsies, had far fewer cases of childbed fever.

Determined to act, Semmelweis observed that chlorinated lime effectively neutralized the foul odor of autopsy tissue. He introduced a rigorous handwashing protocol using this solution for anyone moving between autopsies and patient care. Implemented in mid-May 1847, this simple intervention yielded astonishing results: the mortality rate in the First Clinic plummeted from 18% in April to just 2% by July.

Semmelweis’s discovery laid the foundation for modern antiseptic practices, saving countless lives and earning him the title of a medical pioneer, though his ideas faced resistance during his lifetime.

Politics and Resistance

In the mid-19th century, the medical establishment clung to the humoral theory, which attributed diseases to an imbalance of the body’s four humors. Semmelweis’s radical idea—that a single source, “cadaverous particles” from autopsies, caused childbed fever—was met with skepticism and outright rejection. The notion that physicians, considered gentlemen of high social standing, could spread disease through their hands was unthinkable to many. The prevailing scientific paradigm, coupled with professional arrogance, blinded the medical community to Semmelweis’s evidence. It wasn’t until the 1860s and 1870s, with the advent of germ theory through the work of Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister, that his insights would find broader validation.

In 1848, Semmelweis expanded his protocol, mandating chlorine washing not only for hands but also for instruments in the maternity ward. Despite his efforts to communicate his findings through letters and lectures, his ideas were often misunderstood. Semmelweis argued that decaying organic matter, particularly from cadavers, was the culprit, while contemporaries like Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. believed childbed fever stemmed from a specific contagion spread among patients. These competing theories muddled the reception of his work.

In 1848, Semmelweis expanded his protocol, mandating chlorine washing not only for hands but also for instruments in the maternity ward. Despite his efforts to communicate his findings through letters and lectures, his ideas were often misunderstood. Semmelweis argued that decaying organic matter, particularly from cadavers, was the culprit, while contemporaries like Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. believed childbed fever stemmed from a specific contagion spread among patients. These competing theories muddled the reception of his work.

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 further complicated matters, creating tensions between Semmelweis, a Hungarian, and his conservative Austrian superior, Johann Klein. When Semmelweis’s term as assistant expired, Klein appointed Carl Braun in his place. Semmelweis applied to become a private lecturer but faced rejection, enduring an 18-month wait before securing the position. Frustrated by the Viennese medical establishment’s resistance, he abruptly left for Pest, Hungary, just days after his appointment, unable to tolerate further opposition.

In Pest, the Austrians had quelled the Hungarian revolution, and Semmelweis, a Hungarian, was likely viewed with suspicion. He accepted a low-paying honorary role at a small hospital where childbed fever was rampant. There, Professor Ede Birly, head of obstetrics, attributed the fever to bowel impurities and favored purging as a treatment. After Birly’s death in 1854, Semmelweis assumed the role of professor of obstetrics and successfully implemented his chlorine-washing protocols, dramatically reducing mortality rates.

The Semmelweis Effect

The term “Semmelweis Reflex” or “Semmelweis Effect” emerged as a metaphor for the knee-jerk rejection of new evidence that challenges entrenched beliefs. Semmelweis’s failure to publish his findings promptly contributed to the confusion surrounding his work. In the United Kingdom and United States, his ideas were often misinterpreted as aligning with the contagion theory or the belief that miasmas from dissection rooms triggered childbed fever. Unlike these views, Semmelweis pinpointed cadaverous contamination as the distinct cause, a concept at odds with the pre-germ theory science of the time.

Carl Braun, Semmelweis’s successor, exemplified this resistance. In a textbook, Braun listed 30 causes of childbed fever, attributing only one to cadaverous infection. He cited factors like atmospheric influences, emotional trauma, dietary errors, and uterine pressure as culprits, yet he adopted chlorine washing, maintaining low mortality rates—a testament to the efficacy of Semmelweis’s methods, even if not fully credited.

In 1858, Semmelweis published his seminal essay, The Etiology of Childbed Fever, followed by The Difference in Opinion between Myself and the English Physicians regarding Childbed Fever in 1860. His comprehensive book, The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever, appeared in 1861. Despite these efforts, his ideas were largely ignored or attacked in academic circles, with lecture halls and journals dismissing his theories.

Reaction and Tragic End

The medical establishment’s rejection took a heavy toll on Semmelweis. His frustration grew after the 1861 publication of his book, and he became increasingly outspoken, at times harshly criticizing his detractors as “irresponsible, murdering ignoramuses.” While his accusations reflected the truth of their resistance, his confrontational approach alienated potential allies and hindered his cause.

By 1865, Semmelweis’s behavior was described as erratic. Colleagues Janos Balassa and János Bókai, concerned for his mental state, referred him to a mental institution. Under the pretense of visiting a new facility, Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra lured Semmelweis to the asylum. Realizing the deception, Semmelweis attempted to flee but was brutally beaten by guards, restrained in a straitjacket, and confined to a dark cell. Tragically, he succumbed to injuries from the beating two weeks later, on August 13, 1865, at the age of 47.

Conclusion

The story of Ignaz Semmelweis is a poignant reminder that history often repeats itself, with revolutionary ideas facing fierce resistance from entrenched systems. Semmelweis was undeniably correct—his chlorine-washing protocols saved lives, and his critics, bound by outdated science, were wrong. Remarkably, many of his detractors adopted his methods, as they undeniably worked, even if they refused to fully acknowledge his contributions.

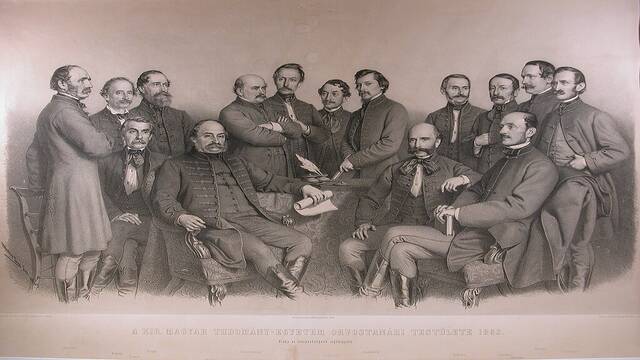

The question lingers: did Semmelweis’s frustration and outspokenness spiral into madness, justifying his institutionalization? Historical accounts, often shaped by those in power, suggest he became irrational, particularly after his 1861 book and 1862 Open Letter. Yet, a 1863 lithograph of the University of Pest’s medical faculty shows Semmelweis standing confidently, arms crossed, among his peers, hinting at his continued prominence.

Semmelweis’s legacy endures as a testament to the power of evidence over dogma and the tragic cost of challenging the status quo. His work laid the groundwork for modern antiseptic practices, proving that one person’s persistence can transform medicine, even in the face of overwhelming opposition.

Historical accounts paint a grim picture of Ignaz Semmelweis in his final years, alleging irrationality, absent-mindedness, severe depression, nervous complaints, an unsteady gait, and rapid aging. Reports claim he remarked, “My head feels weird,” and was accused of embarrassing behavior, excessive alcohol consumption, avoiding family and colleagues, and associating with prostitutes. Such charges, however, read like a character assassination, possibly exaggerated by a medical establishment threatened by his revolutionary ideas. For a man who knew that simple handwashing could save countless mothers and infants from preventable deaths, the frustration of being ignored could understandably lead to distress, particularly if alcohol—a common vice among physicians of the time—was involved.

The critical question remains: could a 47-year-old man, depicted confidently in a 1863 lithograph of the University of Pest’s medical faculty, have descended into madness in just two years, warranting institutionalization by 1865? The answer is likely no. Semmelweis’s intense commitment to his findings and his outspoken criticism of a resistant medical community may have been misconstrued as irrationality, but they reflect a passionate insistence on truth rather than mental instability.

Semmelweis’s autopsy report, difficult to access in English and complicated by inconsistencies between two accounts, provides further insight. It described hyperemia of the meninges and brain, grey degeneration of the spinal cord, gangrene in his right hand’s middle finger, metastatic abscesses, and a putrid stench from large abscesses. The report suggested tabes dorsalis, a degenerative condition linked to untreated syphilis, characterized by symptoms like unsteady gait, personality changes, and dementia, typically manifesting decades after infection. However, the timeline is problematic: Semmelweis’s finger injury, allegedly from a gynecological procedure, was more likely sustained during the violent assault by asylum guards. Tertiary syphilis, requiring 10 to 20 years to progress, could not have developed in the brief period before his institutionalization. Moreover, no prior medical prognosis indicated such a condition before his admission to the Niederösterreichische Landesirrenanstalt, based solely on the referral of Janos Balassa and János Bókai’s medical history.

A second examination in 1963–1964, involving pathological and radiological analysis of Semmelweis’s bones, clarified his cause of death: sepsis from subacute osteomyelitis in his right hand, leading to pyemia (blood poisoning). Modern speculations about Alzheimer’s disease or tertiary syphilis lack credible evidence, as do claims of persecution due to alleged Jewish ancestry. Semmelweis’s Swabian surname and family records, tracing back to his Roman Catholic great-great-grandfather Gyorgy Semmelweis (born 1670), refute such assertions.

Legacy

Ignaz Semmelweis’s tragic end underscores the cost of challenging entrenched beliefs. His relentless advocacy for handwashing, though initially dismissed, revolutionized medicine and saved countless lives. The accusations of madness and moral failings appear less as evidence of personal decline and more as a reflection of a medical establishment unwilling to confront its errors. Semmelweis’s story is a powerful reminder that truth, however inconvenient, can triumph over dogma, even at great personal cost. His legacy endures as a beacon for scientific progress and a cautionary tale of the perils of rejecting innovation.