Ab Absurdo [Latin] From The Absurd

My own mind is my own church. - Thomas Paine

The Absence and the Opposition

Irreligion and antireligion represent two distinct yet overlapping stances within the secular spectrum. Irreligion is the absence of religious belief or practice—a passive disengagement that ranges from apathy to deliberate non-affiliation. Antireligion, by contrast, actively opposes religion, viewing it as a source of division, ignorance, or societal harm. Together, they form a broader rejection of religious frameworks than atheism’s focus on deities, embodying both indifference and resistance. This article, the second of 17 in our 18-part secularism series, explores the historical roots, core principles, global variations, and contemporary relevance of irreligion and antireligion, probing their roles in a world seeking meaning without faith. As Thomas Paine’s declaration suggests, these stances prioritize individual autonomy, yet they raise questions: Does indifference sustain freedom, or does opposition risk new dogmas?

Irreligion encompasses those who live without religious commitment, from the casually unaffiliated to those who consciously reject faith’s role in their lives. Antireligion takes a more confrontational approach, critiquing religion’s influence on culture, politics, or morality. Both challenge the centrality of religion in human affairs, but their methods differ—irreligion through detachment, antireligion through activism. This duality invites scrutiny: Can irreligion provide a foundation for meaning, or does it drift into apathy? Does antireligion liberate or foster intolerance? This exploration navigates these tensions, mapping two paths in the secular landscape.

Historical Context

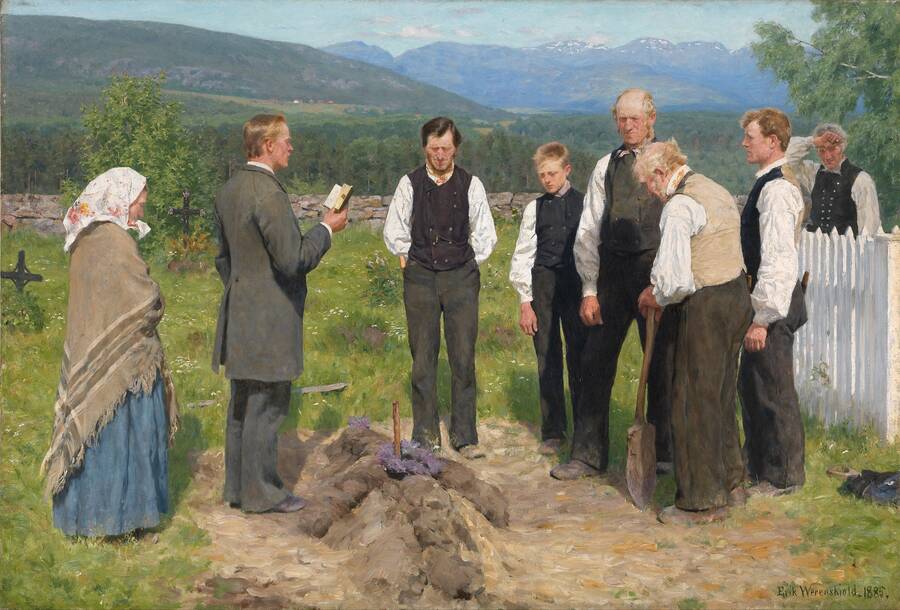

Irreligion and antireligion trace their origins to diverse historical moments. Irreligion appeared in ancient societies where individuals or communities sidestepped religious rituals, such as Confucian scholars prioritizing ethics over divinity. The Enlightenment fostered irreligion through deism, with thinkers like Paine and Jefferson embracing reason over organized faith. Antireligion emerged more forcefully in the 19th century, as anarchists like Mikhail Bakunin and freethinkers like Annie Besant denounced religion as a tool of oppression. The 20th century saw irreligion grow in secular states like France and Japan, while antireligion fueled movements against clerical power, from Mexico’s Cristero War to Soviet anti-religious campaigns. Today, both shape global debates, from secular policy to cultural identity, yet face accusations of fostering apathy or zealotry.

Core Principles

Irreligion and antireligion share a rejection of religious authority but differ in approach:

- Irreligion: Emphasizes neutrality, living without religious frameworks. It is less a philosophy than a state of being, often paired with secular practices like humanism or rationalism.

- Antireligion: Actively critiques religion’s societal role, arguing it perpetuates division or control. It seeks to diminish religious influence in public and private spheres.

Neither offers a moral or cosmological system, relying instead on reason and human agency. Paine’s assertion of the mind as a “church” reflects irreligion’s autonomy, but critics question whether indifference risks cultural drift or if opposition mirrors the dogma it rejects.

Global Variations

Irreligion thrives in regions like East Asia, where Japan’s cultural non-belief blends Shinto and Buddhist traditions with minimal religious adherence. In Scandinavia, high rates of irreligion underpin secular welfare states. Antireligion, by contrast, is prominent in areas with strong religious institutions, such as Latin America, where activists challenge Catholic influence in politics, or India, where rationalist movements confront Hindu nationalism. In Europe, antireligion often takes intellectual forms, as seen in France’s Laicist tradition. These variations highlight diverse secular expressions, but also tensions—irreligion’s detachment can seem passive, while antireligion’s activism risks alienating spiritual communities.

Modern Relevance

Irreligion and antireligion shape contemporary society in distinct ways. Irreligion informs secular education, where curricula prioritize science and ethics over scripture, and supports neutral governance in countries like Canada and Australia. Antireligion drives movements to remove religious symbols from public spaces, as seen in debates over crosses in European courthouses or prayers in U.S. schools. Both influence cultural shifts, from art celebrating human agency to policies promoting inclusivity. Yet critics argue irreligion fosters nihilism, leaving societies without shared values, while antireligion’s confrontational stance can deepen divisions. Their challenge is to balance autonomy with cohesion, ensuring secularism remains inclusive rather than exclusionary.

Critiques and Challenges

Irreligion’s strength—its lack of commitment—can lead to cultural disconnection, as communities lose shared rituals without replacing them. Antireligion, while energizing, risks intolerance by dismissing religion’s cultural or emotional value. Some argue irreligion enables a utilitarian worldview, prioritizing efficiency over meaning, while others see antireligion as cultural erasure, alienating believers. Proponents counter that irreligion frees individuals to define their own values, and antireligion exposes religion’s harms. The tension, as Paine’s quote implies, lies in ensuring autonomy doesn’t become apathy or opposition doesn’t mimic the zeal it critiques.