Vahdat-e-Bashar [Persian] - Unity of Mankind

The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens. — Baháʼuʼlláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Baháʼuʼlláh (CXXVII)

Origins and History

The Baháʼí Faith, one of the world’s youngest major religions, was founded in 19th-century Persia (modern-day Iran) by Mírzá Husayn-ʻAlí Núrí, known as Baháʼuʼlláh (1817–1892), meaning “Glory of God.” Emerging from the Bábí movement, it began in 1844 when Siyyid ʻAlí-Muhammad, known as the Báb, announced himself as a messenger preparing the way for a greater revelation. Baháʼuʼlláh, a follower of the Báb, declared in 1863 that he was the promised messenger, establishing the Baháʼí Faith. Facing persecution in Persia, Baháʼuʼlláh was exiled to the Ottoman Empire, where he developed the faith’s teachings. His son, ʻAbduʼl-Bahá, spread the religion globally, and his great-grandson, Shoghi Effendi, formalized its administrative structure. Despite ongoing persecution in Iran, the Baháʼí Faith has grown to approximately 5–8 million adherents, with communities in over 200 countries, including significant populations in India, the United States, and Africa.

Core Beliefs

The Baháʼí Faith is a monotheistic religion emphasizing the unity of God, religion, and humanity. Key tenets include:

- Unity of God: There is one God, creator of all, known by different names across faiths.

- Unity of Religion: All major religions come from the same divine source, with progressive revelations from messengers like Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, and Baháʼuʼlláh.

- Unity of Humanity: All people are equal, regardless of race, gender, or class, and should work toward global harmony.

- Independent Investigation of Truth: Individuals must seek truth through reason and spiritual inquiry, free from dogma.

- Harmony of Science and Religion: Both are complementary paths to truth.

- Social Principles: These include gender equality, universal education, elimination of prejudice, and world peace.

Baháʼís strive to live ethically, fostering unity and justice while preparing for a global civilization rooted in spiritual values.

Practices

Baháʼí practices emphasize devotion, service, and community building:

- Prayer and Meditation: Daily obligatory prayers (three options) and meditation on sacred writings, such as Baháʼuʼlláh’s texts, foster spiritual growth.

- Fasting: Baháʼís aged 15–70 fast annually from March 1–19 (Naw-Rúz), abstaining from food and drink from sunrise to sunset.

- Community Gatherings: Regular “Feasts” (every 19 days) combine worship, consultation, and socializing, strengthening community bonds.

- Service and Education: Baháʼís engage in community service, such as literacy programs or social development projects, and study circles for spiritual education.

- Holy Days and Festivals: Key celebrations include Naw-Rúz (New Year), Ridván (commemorating Baháʼuʼlláh’s declaration), and the Birth of Baháʼuʼlláh.

- No Clergy: Spiritual guidance comes from elected institutions, not priests, emphasizing collective responsibility.

These practices integrate faith into daily life, promoting personal growth and global unity.

Sacred Texts

The Baháʼí Faith’s sacred texts, primarily in Persian and Arabic, are considered divine revelations. Key writings include:

- Kitáb-i-Aqdas: Baháʼuʼlláh’s “Most Holy Book,” outlining laws, ethical principles, and administrative guidelines.

- Kitáb-i-Íqán: The “Book of Certitude,” explaining the unity of religions and spiritual truths.

- Gleanings from the Writings of Baháʼuʼlláh: A compilation of key teachings on theology and ethics.

- Writings of the Báb, ʻAbduʼl-Bahá, and Shoghi Effendi: These include letters, prayers, and interpretations, guiding practice and administration.

Baháʼís study these texts in their original languages or translations (widely available in English and other languages), often in communal settings. The texts are treated with reverence, guiding personal and collective life, with ongoing efforts to translate them globally.

Denominations and Diversity

The Baháʼí Faith is highly unified, with no formal sects, due to its centralized administrative structure led by the Universal House of Justice, established in 1963 in Haifa, Israel. However, cultural diversity exists:

- Global Communities: Baháʼís in Africa, Asia, and the West adapt practices to local cultures, such as incorporating traditional music in worship or community projects tailored to regional needs.

- Orthodox vs. Liberal Interpretations: Minor differences arise over emphasis on strict adherence to laws versus flexible application, but these are resolved through consultation.

- Covenant-Breakers: Rare dissident groups rejecting the authority of Baháʼuʼlláh’s successors are excluded from the community but are marginal.

The faith’s universalist ethos and lack of clergy foster unity, with diversity expressed through global initiatives like interfaith dialogue or localized service projects.

Worship and Community

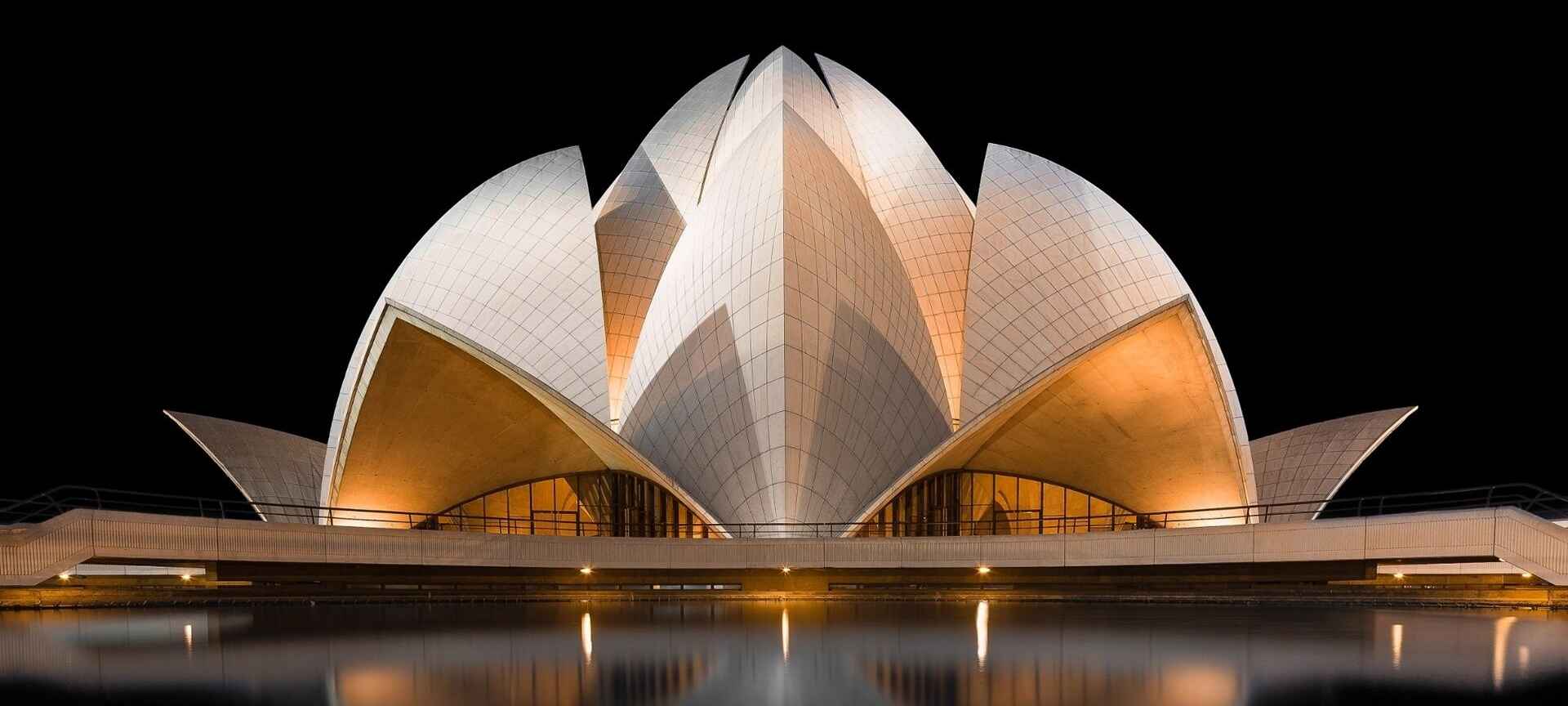

Baháʼí worship occurs in homes, community centers, or Houses of Worship (e.g., the Lotus Temple in Delhi), which are open to all faiths and focus on prayer, music, and scripture readings. Communities gather for Nineteen Day Feasts, study circles, and children’s classes, emphasizing spiritual and social development. Baháʼí institutions, like Local and National Spiritual Assemblies, elected democratically, coordinate activities and service projects, such as schools or environmental initiatives. In the diaspora, Baháʼís maintain identity through global conferences, digital platforms (e.g., online devotionals), and interfaith outreach, aligning with the faith’s focus on unity and inclusion.

Art and Cultural Practices

Baháʼí art reflects its global and spiritual ethos, with minimal iconography to avoid idolatry. Notable expressions include the architecture of Houses of Worship, like the lotus-shaped temple in India or the terraced gardens in Haifa, symbolizing unity and beauty. Calligraphy of Baháʼuʼlláh’s writings in Persian and Arabic adorns sacred spaces. Music, including devotional songs in diverse cultural styles, enhances worship. Narrative art, such as illustrated histories of the Báb or Baháʼuʼlláh, serves educational purposes. Modern media, like films or digital archives, promote Baháʼí values. Cultural practices, such as Naw-Rúz celebrations with shared meals, blend Persian roots with global traditions, emphasizing hospitality and unity.

Early vs. Later Teachings

Early Baháʼí teachings, from the Báb and Baháʼuʼlláh, focused on spiritual renewal, unity of religions, and divine revelation, addressing Persia’s social and religious turmoil. Baháʼuʼlláh’s later writings, like the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, formalized laws and social principles, such as gender equality and universal education. ʻAbduʼl-Bahá’s global travels (1911–1913) emphasized practical application, like peace advocacy, while Shoghi Effendi’s leadership structured the administrative order. Modern Baháʼí practice applies these teachings to contemporary issues, such as sustainable development, racial unity, and global governance, while retaining the core focus on spiritual and social transformation.

Persecution and Challenges

Baháʼís have faced severe persecution, particularly in Iran, where they are denied citizenship rights, face imprisonment, and are barred from higher education. Historical executions of the Báb and early followers set a precedent for ongoing discrimination. In other countries, Baháʼís occasionally face suspicion due to their emphasis on global unity, mistaken for political agendas. In the diaspora, challenges include maintaining community cohesion amid cultural assimilation and addressing misconceptions about the faith’s universalist claims. Baháʼís counter these through advocacy, international appeals (e.g., to the UN), and community resilience, emphasizing service and dialogue.

Controversies and Modern Debates

The Baháʼí Faith faces debates over its strict covenant against schisms, which some view as rigid, though it ensures unity. Gender roles spark discussion, as women are equal but excluded from the Universal House of Justice, prompting varied interpretations. The faith’s rejection of partisan politics creates tension for members in politically charged contexts, though most embrace neutrality. Adapting traditional practices, like fasting, to modern schedules or global diversity raises practical questions. The emphasis on consultation and unity helps resolve these issues, while digital platforms and global conferences foster dialogue on balancing tradition with contemporary needs.

Contemporary Context

The Baháʼí Faith thrives globally, with vibrant communities in diverse regions, from rural Africa to urban centers like Chicago and Sydney. Houses of Worship and community centers serve as hubs for worship, education, and service, such as health clinics or youth empowerment programs. Digital tools, like online study courses or virtual Feasts, expand access to teachings. The faith’s focus on unity drives activism in areas like climate change, gender equality, and peacebuilding, often through UN-affiliated NGOs. Challenges include ongoing persecution in Iran and sustaining growth in secular societies. The Baháʼí vision of a unified world resonates in addressing global crises, promoting a universalist spirituality.